In the brilliant classics Douglas Adams ‘ “Hitchhiker’s guide to the galaxy” had a few animals smarter than people. One thing — not without irony — was the common laboratory mouse. Other creature knew about the intergalactic bulldozers, which in the end would vaporize the planet, and tried to warn us about the impending fate. The last Dolphin message was misinterpreted as a surprisingly sophisticated attempt to do a double somersault through a Hoop, whistling a merry tune, but in fact the message was this: “All the best and thanks for all the fish!”.

They say the dolphins have an unusual level of intelligence that differentiates and elevates them above the rest of the animal world. It is widely believed that dolphins are very smart (maybe smarter than humans), have a complex behavior and have the ability protetyka. However, in recent times against the background of studies of these animals have developed several different, sometimes opposite opinion.

The superiority of the dolphins

The exalted status of dolphins in animals came with John Lilly, the Dolphin researcher 1960-ies and lover of psychotropic drugs. He first popularized the idea that dolphins are smart, and later even suggested that they are smarter than people.

In the end, after the 1970s, Lilly was largely discredited and not made a great contribution to the science of Dolphin cognition. But despite the efforts of the scientists the main thread designed to distance himself from his quirky ideas (the dolphins were spiritually enlightened), and even the most insane (which dolphins communicate holographic images), his name is inevitably associated with studies on the dolphins.

“He is, and I think most scientists delfinopolis will agree with me, the father of the study of Dolphin intelligence,” writes Justin Gregg in the book “are dolphins smart?”.

Since Lilly’s studies of dolphins have shown that they understand the signals transmitted by the television screen, there are parts of their bodies, recognize their own image in the mirror and have a complex repertoire of whistles and even names.

In any case, all these ideas lately subject to doubt. The book of Gregg is the latest tug of war between neuro-anatomy, behavior, and communication between ideas that the dolphins are special and that they are on the same level with many other creatures.

Why large brains

Still debunking abilities of dolphins concerned two main topics: anatomy and behavior.

In 2013, the anatomist Paul Munger has published an article in which he substantiated his position that the large brain of a Dolphin has nothing to do with intelligence.

Munger, a researcher from the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa, have previously argued that the large brain of a Dolphin is likely to have evolved to help the animal keep warm than to perform cognitive functions. This article is from 2006 have been widely criticized by the research community of delfinopolis.

In his new work (also written by the Manger), he undertakes a critical approach to the study of the anatomy of the brain, the archaeological record and frequently mentioned behavioral studies, concluding that cetaceans are not smarter than other invertebrates, and that their large brains appeared to be. This time he cites many behavioral observations like recognition of the image in the mirror, which was held in September 2011 and appeared at the end to Discover. Munger found them to be incomplete, incorrect or outdated.

Lori Marino, neuroanatomy of Emory University, who plays for the intelligence of the brain, is working on a rebuttal.

Smarter!

Another argument is that the behavior of dolphins is not as impressive as they say — leads Gregg. As a professional researcher of dolphins, he notes that he respects the “achievements” of dolphins in the area of knowledge, but feels that the public and other researchers have slightly overstated their actual level of cognitive ability. In addition, many other animals demonstrate the same impressive features.

In his book Gregg refers to experts who have questioned the value of the test of self-perception in the mirror, who is believed to indicates some degree of self-awareness. Gregg notes that octopus and pigeons can behave like dolphins, if you give them a mirror.

In addition, Gregg argues that communication dolphins are overrated. Although their whistles and clicking, of course, are complex forms of audio, they, nevertheless, do not have features characteristic for human language (like the conclusion of the final concepts and meanings or freedom from emotions).

In addition, he criticizes attempts to apply information theory — branch of mathematics — to the information contained in the dolphins. Whether it is possible to apply information theory to animal communication? Gregg questioned, and he is not alone.

Gregg emphasizes that the dolphins certainly have many impressive cognitive abilities, but many other animals too. Not necessarily the most intelligent: many chickens are as intelligent in some problems, like dolphins, says Gregg. Spiders also exhibit a striking capacity for learning, but they have altogether eight eyes.

Craving for knowledge

It is important to note that researchers like manger are in the minority among scientists studying the cognitive abilities of dolphins. Moreover, Gregg is trying to distance itself from thoughts of mediocrity dolphins — he says that other animals are smarter than we thought.

Even Gordon Gallup, a neuroscientist-a behaviorist who was the first to use a mirror to assess the presence in primates of self-consciousness, expresses doubt that dolphins are capable of it.

“In my opinion, the videos captured during this experiment is not convincing,” he said in 2011. “They are suggestive, but not convincing”.

The arguments against the exclusivity of the dolphins and focus on three main ideas. First, according to Munger, the dolphins just are not smarter than other animals. Second, to compare one type with another is difficult. Third, too few studies to make strong conclusions.

Despite his reputation as an animal with exceptional intelligence, dolphins can be not as smart as they thought.

Scott Norris, writing in Bioscience, commented, “the ingenious Scott Lilly” has made a great contribution in building an image of “smart Dolphin” in the 1960-ies. He was fascinated by the dolphins and spent years to teach them to talk. Lilly’s experiments were unethical, sometimes even immoral, but he not only tried to teach the language of animals, which was attributed to the beginnings of intelligence. Complex communication are born out of social systems and social interactions require other traits that are often associated with intelligence. To form and remember social connections, learn new behaviors and work together, we need a culture.

From this point of view, dolphins do exhibit behaviors and practices associated with culture and intelligence. Norris notes that studies wild dolphins and whales show that their vocalization is quite diverse and specific, so that it can be considered a language. Dolphins can easily learn new behavior and is even able to simulate. They keep track of complex social hierarchies within and between groups. They have even been known to invent new behaviors in response to new situations, and this, according to Norris, some scholars believe “the most distinctive trait of the intellect.” Moreover, dolphins can even teach each other these new practices behavior. Norris describes how the populations of some dolphins used sponges to protect from scratches and have taught others this technique. This transfer of practices is considered by many as the origin of culture.

Yes, the dolphins seem more intelligent than many species, but their behavior is in no way unique to dolphins. Many animals, such as boars, dogs, primates or sea lions, have a complex vocalization, social relationships, learning ability, imitation of and adaptation to new situations as complex. Many skills, particularly teaching, other species have developed stronger than dolphins. The cultural exchange that has yet to prove to the dolphins, is less common, but other animals are still not well understood. Can be identified and other examples.

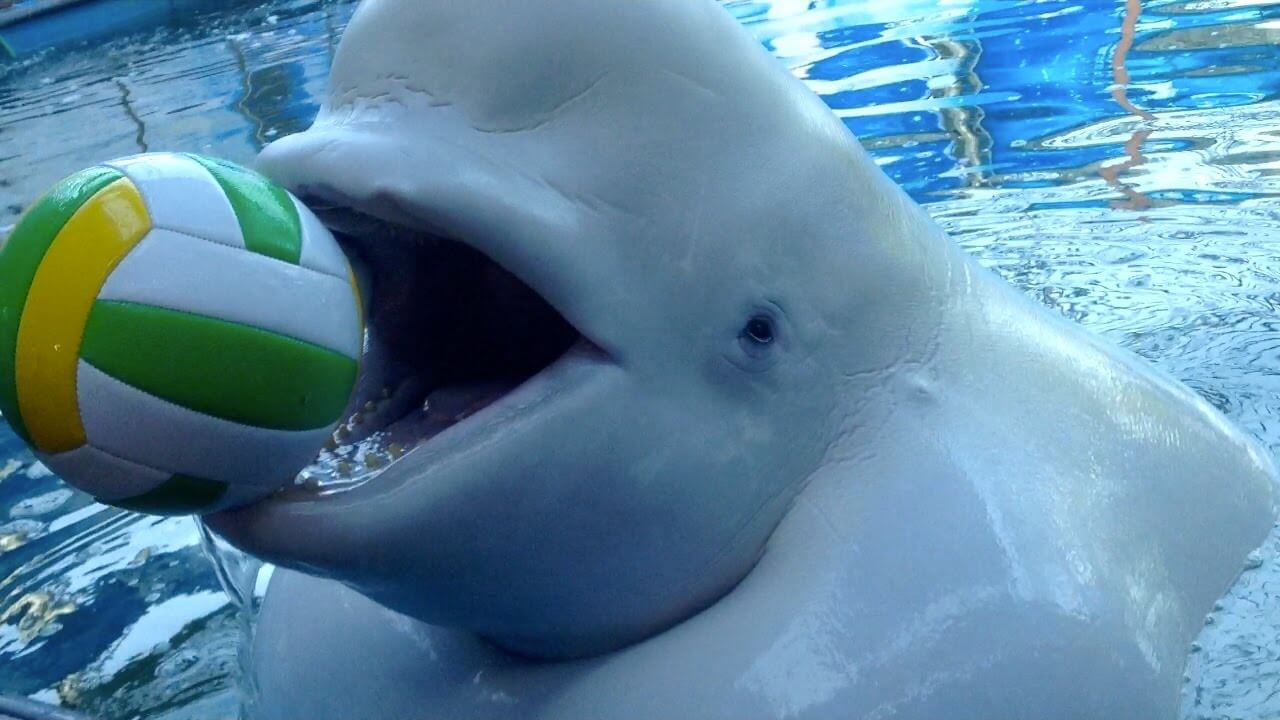

The problem is not only and not so much how smart dolphins are, because at some level they are really smart, but they smarter than other animals, and this is still unknown. Dolphins love to ascribe human traits. Many dolphins you can see the “face” and “smile” can not be said, for example, of the wild boar. Looking at that grinning face, we begin to see dolphins in people. How smart dolphins are? It all depends on how smart you want them to see.

Whether dolphins are as smart as they say?

Ilya Hel