Sometimes the human mind can be so outstanding that will change the world. We don’t know why these people are superior to others, but science is trying to find the answer to this question.

In the medical history Museum of mutter in Philadelphia there are many special medical samples. Downstairs in a glass vessel floats fused liver of the 19th century Siamese twins Chang and ang. Nearby visitors can take a look at the hands, swollen from gout, bladder stones of chief judge John Marshall, a cancerous tumor extracted from the jaw of President Grover Cleveland, and the femur of the civil war soldier, in which you can still see the bullet. But there is one exhibit at the entrance which causes the awe. Look carefully at the stand, and you will see the prints of sweaty foreheads left by visitors to the Museum, clinging to the glass.

An object that fascinates them, is a small wooden box with 46 microscopic plates, each of which is placed a slice of the brain of albert Einstein. Magnifying glass, located above one of the slides shows a piece of fabric the size of a postage stamp, its graceful branches and curves, reminiscent of the mouth of the river from the height of bird flight. These remnants of the brain are fascinating, not least because of the astonishing merits of the famous physicist, though nothing about them saying. On the other stands in the Museum show the diseases and deviations, when something went wrong. But Einstein’s brain is a potential, exceptional ability of the mind of a genius that surpassed many. “He saw wrong, like everybody else,” said visitor Karen O’hara, looking at a sample of the tea color. “And he could go beyond what you can see, and it’s fantastic.”

Throughout human history there were individuals who made important contributions to their field of work. Michelangelo was a genius of sculpture and painting. Marie Curie is a scientific insight. “Genius,” wrote German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, “the lights of his time like a comet on the way to the stars”. Consider Einstein’s contribution to physics. Without any sophisticated tools at hand, but his own thoughts, he predicted in his General theory of relativity is that accelerating massive objects like black holes, rotating around one another, will create ripples on the surface of space-time. It took a hundred years, a lot of computing power and extremely sophisticated technology to finally confirm his innocence — a physical proof of the existence of gravitational waves came less than two years ago.

Einstein revolutionized our understanding of the very laws of the Universe. But our understanding of how worked his mind remains mundane. What distinguishes his brainstorm, his thought processes, his brilliant colleagues? What makes a genius a genius?

Philosophers have long been debating on the origins of genius. Ancient Greek thinkers believed that an excess of black bile — one of the four bodily components, referred to by Hippocrates, — gives the poets, philosophers, and other high souls “by the power of exaltation,” says the historian Darrin McMahon. The phrenologists tried to find genius in the cones on the head; craniometry collected the skull including the skull of the philosopher Immanuel Kant — who then weighed, tested, measured.

None of them found any source of genius, and it is certainly unlikely that such a thing can be found. Genius is too elusive, too subjective, too embedded in history that it can be easy to select. And it requires a terminal expression too many features to be simplified to points, faces, the human person. Instead, we can try to understand him, revealing the complex interwoven qualities — intelligence, creativity, perseverance, success, and this is not a comprehensive list — which create the person who can change the world.

Intelligence is often considered the measure of genius of the measured quality, which leads to incredible achievements. Lewis Terman, a psychologist at Stanford University who helped invent the test for intelligence quotient (IQ), believed that such a test can reveal genius. In the 1920-ies it was watched by more than 1500 California schoolchildren with IQs above 140 is considered “genius, or almost genius” — to find out how they behave in life in comparison with other children. Terman and his colleagues observed the participants (calling them “termites”), their way of life and for success, documenting them in notes Genetic Studies of Genius. This group included members of the National Academy of Sciences, politicians, doctors, professors and musicians. Forty years after the start of the study, the scientists documented thousands of scientific papers and books that they published, the number of patents issued (350) and written stories (about 400).

Monumental intellect itself does not guarantee a monumental achievement, as found by Terman and his colleagues. Some members of the study failed to break through to success, despite the high level of intelligence. Some were expelled from the College. Others also explored, but the IQ which is not very tall, became known in his field, among them Luis Alvarez and William Shockley, Nobel laureates in physics. Charles Darwin was “a very ordinary boy, not possessed of great intelligence.” And as an adult, he solved the riddle of the incredible diversity of life.

Scientific breakthroughs like Darwin’s theory of evolution would not be possible without the creative sides that no one, not even Thurman could not be measured. But creativity and its processes can be explained, to some extent, using the most creative people. Scott Barry Kaufman, scientific Director of the imagination Institute in Philadelphia, United people, who were considered pioneers in their fields of activity — like the psychologist Steven Pinker, comedian Anne Libera — to discuss with them their ideas and insights. Kaufman’s goal was not to find out genius — in the end, he believed that the word exalt some, but belittles many others — and to develop the imagination of all the others.

These interviews showed important moment: the flash of insight that occurs at an unexpected time — during sleep, in the shower or on a walk — often occurs after a period of contemplation. Information is received consciously, but the problem is processed unconsciously, allowing the solution to pop up when the mind least expects it. “Great ideas do not come if you are trying to focus on them,” says Kaufman.

The study of the brain can point out how there are these moments of insight. The creative process, says Rex Jung, a neuroscientist from the University of new Mexico, is based on a dynamic interaction of neural networks that work together and arising from different parts of the brain simultaneously — the right and left hemisphere, and regions of the prefrontal cortex. These networks ensure our ability to meet external requests is an activity that we should exercise, work and pay taxes, and the like — and are located mostly in the outer parts of the brain. Others cultivate the internal processes of thinking, including the reverie and imagination, and extend mostly to the middle area of the brain.

Jazz improvisation is a compelling example of how neural networks interact during the creative process. Charles Limb, a specialist in hearing and aural surgeon at the University of California in San Francisco have developed a small keyboard without iron, which can be played within an MRI scanner. Six jazz pianists were asked to play the famous party, and then improvise a solo, listening to the sounds of a jazz Quartet. Their scans showed that brain activity was “completely different” when the musicians improvised, says Limb. Internal network connected with expression, showed an increase in activity, while other networks related to the focus and self-control, calm down. “If the brain has disabled the ability of self-criticism,” say the researchers.

This could explain the incredible level of jazz pianist Keith Jarrett. Jarrett, who was capable of improvisation to give concerts up to two hours, could not explain — or rather, thought was impossible — as it comes music. But when he sat in front of his audience, he deliberately pushes out the notes from your brain, allowing your fingers to pristukivajut keys without any external pressure. “I fully let go of consciousness,” he says. “I’m driven by my power that I can only thank”. Jarrett says one of the concerts in Munich when he felt dissolved in the higher notes of the keyboard. His incredible creativity, nurtured by decades of listening, learning and practising the tunes, manifests itself when he least controls it. “It’s a huge space in which appears the music in which I believe.”

One of the hallmarks of creativity is the ability to create relationships between seemingly disparate concepts. The close weave between the different parts of the brain provide a intuitive exchange between them. Andrew Newberg, Director of research at the Institute for integrative health Marcus at the University hospital of Thomas Jefferson, is using diffusion tensor visualization, the method of contrast MRI, which mapped the neural pathways in the brains of creative people. The participants, who came from a group of thinkers Kaufman, pass standard tests of creativity, which require them to find a new use for everyday objects like baseball bats and toothbrushes. Newburgh seeks to map the relationship in the minds of the great thinkers of connections in the brains of the control group to see if there are any differences in how different areas of their brains interact. His ultimate goal is to scan 25 individuals in each category and then analyzing the data to evaluate the similarities and differences in each group. For example, whether specific regions of the brain of a comedian is more active than in the brain of a psychologist?

A preliminary comparison of one “genius” — Newburgh freely uses that word to separate participants and one control showed an intriguing contrast. When scanning the brain of the participant was divided into red, green and blue portions of the white matter that contain weave, allowing neurons to transmit electrical messages. The red area in each image is the corpus callosum, a bundle of over 200 million nerve fibers connecting the two brain hemispheres and facilitates communication between them. “The more red you see,” says Newberg, “the more connective fibers”. The difference is quite obvious: a red segment of the brain of a “genius” twice as wide as the red segment of the control brain.

“This means that between the left and right hemispheres do more communication, and this would be expected from extremely creative people,” says Stewart, stressing that the study is still going on. “In a thought process more flexibility, more of a contribution from different parts of the brain.” Green and blue plots show the connectivity of other areas stretching from front to rear, including the dialogue between the frontal, parietal and temporal lobes, and may reveal additional facts. Newburgh is not yet going to talk about what else you can learn. This is only one part.

Yet neuroscientists are trying to understand how the brain contributes to the development of paradigm-changing thought processes, other scholars wonder where and why developing this ability. Geniuses are born or made? Francis Galton, cousin of Darwin, were protesting against the “claim to natural equality”, believing that genius comes from family lineage. To prove it, he made the tree pedigrees of European leaders in different industries — from Mozart and Haydn to Byron, Chaucer, Titus and Napoleon. In 1869, Galton published his results in Hereditary Genius, the book that reignited the argument of “nature versus nurture” and spawned the infamous area of eugenics. Galton came to the conclusion that geniuses were rare, about one in a million. But what was unusual is many examples in which “people, that nothing of itself is not represented, had prominent relatives.”

Advances in the study of genetics has made possible the study of human traits on a molecular level. Over the past few decades, scientists have tried to find genes associated with intelligence, behavior and even unique qualities like perfect pitch. In the case of intelligence this has given rise to ethical concerns on the possible use of the findings. Also, all of this is very difficult because thousands of genes each with a small contribution. How about the abilities of another kind? Whether perfect pitch can be innate? Many prominent musicians, including Mozart and Ella Fitzgerald, as I believe, possessed perfect pitch, which has played an important role in their extraordinary careers.

Only one genetic potential promises the actual implementation. Genius necessary to bring up. Social and cultural influences can be a breeding ground that creates genius in a certain moment of history: Baghdad during Islam’s Golden age, Calcutta during the Bengal Renaissance, the Silicon valley today.

A hungry mind can also find the intellectual stimulation needed in the home — as in the case of Terence Tao in suburban Adelaide, Australia, which is considered one of the greatest minds currently working in the field of mathematics. Tao has demonstrated a remarkable understanding of language and numbers early in life, but his parents have created an environment in which this understanding would flourish. They gave him books, toys and games, encouraging play and learn on their own — his father Billy believed that stimulates originality and ability to solve problems with his son. Billy and his wife grace also sought additional opportunities to teach his son when he began his formal education, and he was lucky to find teachers who further strengthened and directed his mind. Tao entered the secondary school at the age of seven years, scored 760 points in math at the age of eight, he entered the University at age 13 and became a Professor at the University of California Los Angeles in 21 years. “Talent is very important,” he once wrote in a blog, “but more importantly, how it develops and is nurtured”.

The gifts of nature and the environment education will not be able to nurture a genius without motivation and perseverance. These personality traits that made Darwin spend twenty years perfecting his “Origin of species”, and the Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan of producing thousands of formulas, and inspire the work of the psychologist Angels Duckworth. She believes that the combination of passion and perseverance — she calls it the “core” — leads people to success. Duckworth, “genius” MacArthur Foundation Professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, said that the word genius too easily covered with a layer of magic, though major advances are born spontaneously, without hard work. She believes that there is a difference between individual talent of a person, but no matter how brilliant will this talent, perseverance and discipline is extremely important for success. “When do you see someone who is trying to achieve something great, his efforts do not go unnoticed”.

And of course, nothing happens the first time. “The first criterion of the result is a performance, hard work,” says Dean Keith Simonton, Professor Emeritus of psychology at the University of California at Davis and a longtime researcher of genius. Big breakthroughs happen after many attempts. “Most of the articles published in science, no one has ever been cited,” says Simonton. “Most of the songs never played. Most of the artworks have never been exhibited”. Thomas Edison invented the phonograph and the first commercially viable light bulb, but they were just two of thousands of U.S. patents that he registered.

Lack of support can stop the future development of genius; they may not get a chance to prove himself. For a long time, women were denied formal education, they underestimate their accomplishments and let their professional activities. An older sister, Maria Anna Mozart, a brilliant harpsichordist, terminated his career at the behest of his father, when he reached the age of marriage at 18 years. Half of the women in the study, Terman became Housewives. People born in poverty or in terrible conditions, not getting the chance to work on anything else except their own survival. “If you think genius can be identified, to cultivate and nurture, says the historian Darrin McMahon — what an incredible tragedy is the premature death of thousands of geniuses, both recognized and not.”

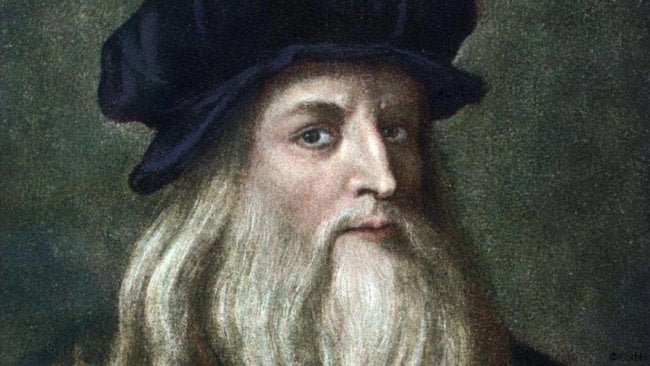

Sometimes, by pure luck, the ability and desire to find each other. If the world ever lived a man who embodies the genius in each cell, it was Leonardo da Vinci. Born in 1452, Leonardo began life in a stone house in the Italian Tuscany, where olive trees and dark blue clouds hid the Arno valley. From the simple beginning of the intelligence and skill of Leonardo soared as the same comet Schopenhauer. The breadth of his abilities — of his creative skills, his understanding of human anatomy, his prophetic engineering skills were not equal.

The road to genius, Leonardo began apprenticeship with the master of fine arts Andrea del Verrocchio in Florence, when he was a teenager. Creative talent of Leonardo was so powerful that during his life he filled thousands of pages in their notebooks, given the hundreds of studies and projects, from optical to mechanical. He persisted regardless of the problem. “The hurdles didn’t stop me,” he wrote. Leonardo also lived in Florence of the Italian Renaissance, when art was cultivated by wealthy patrons and talents literally came from the streets, including Michelangelo and Raphael. Then the art was still a craft.

Leonardo could see the impossible — to hit the target, wrote Schopenhauer, “which others have not even seen.” Today an international group of scientists and researchers are actively exploring the life of Leonardo himself. In the framework of the Leonardo Project tracked the genealogy of the artist and conducted a DNA search to find out more about the pedigree and physical characteristics of the wizard, confirm the authorship of paintings attributed to him, and, importantly, to find clues to his unusual talents.

Member of the team working on this project, David Karamelli works in high-tech laboratory of molecular anthropology at the University of Florence, which is located in 16-storey building with a magnificent view over Florence. There are visible the domes of Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, the tops of which were originally made by Verrocchio and raised up with Leonardo in 1471. This juxtaposition of past and present leitmotif runs on the examination of ancient DNA, which holds Karamelli. Two years ago he published a preliminary genetic analysis of Neanderthal skeleton. Now he is ready to apply such methods to DNA of Leonardo, which his team hopes to extract from biological relics — bones artist, hair strands, skin cells left on your notebooks or even saliva, which Leonardo used for the preparation of the canvases.

It is an ambitious plan, but team members are optimistic. Genealogists tracing the living relatives of Leonardo, to confirm the authenticity of the DNA of the masters, if you find her. Physical anthropologists are trying to access the remains of Leonardo, who, as expected, are stored in the Amboise castle in the Loire valley in France, where he was buried in 1519. Critics and genetics, including the specialist of Institute of genomics Craig Venter, experimenting with techniques to obtain DNA from fragile figures and works of the Renaissance. “The wheels zavraschalsya,” says Jesse Ausubel, Vice-President of the Foundation Richard Lounsbery coordinating the project.

One of the first tasks of the group is to explore the possibility that the genius of Leonardo depended not only on his intellect, creativity and cultural environment, but also on the strength of the perception of the master. “Just as Mozart had extraordinary hearing,” says Ausubel, “Leonardo could have extraordinary visual acuity”. Some genetic components of view is well identified, including genes of red and green pigments are located on the X chromosome. Thomas Sakmar, a specialist in sensory neuroscience at Rockefeller University, says scientists can explore the genome to find out whether the Leonardo unique variations which changed his color perception, and allowed you to see more shades of red and green.

The project team Leonardo does not know for sure where to look for answers to their questions, how to explain the incredible ability of Leonardo to find out birds on the fly. “He seemed to do the stroboscopic photos in the freeze frame,” says Sakmar. “It may well be that this was associated with certain genes.”

The desire to uncover the origin of genius may never lead to results. As the universe, the genius of the human care of us and at the same time hides its secrets.

What makes a genius a genius?

Ilya Hel