Human cloning has become a very popular subject of science fiction, and we are desperate to wait for him to step over from the pages and screens in real life. However, in fact, we can be much closer to it than usual for us sci-Fi heroes. At least from the point of view of science. The obstacles that stand between us can be less associated with process and more with its potential consequences, and ethical war. Although science has come a long way in this direction in the last century, when it came to cloning, zoo animals, humans and primates, there was always an insuperable obstacle. We have already learned how to clone the cells of people. What’s next?

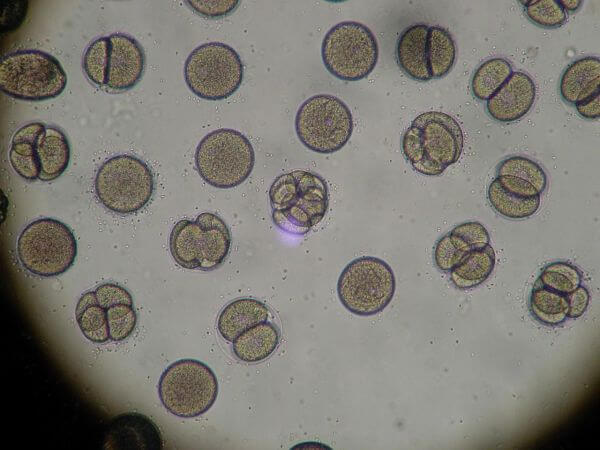

Surprisingly challenging the concept of cloning is a rather simple (in theory, at least) practice: you need to take two cells of the same animal — one of them is the egg from which you’ve removed the DNA. You take DNA from another somatic cell and placed her inside devoid of DNA cells. Any offspring of that cell will be genetically identical to the parent cell. While in humans reproduction is the result of combining two cells (one from each parent, each with its own DNA), the method of cellular photocopies really takes place in nature. Bacteria are reproduced in the process of double division: each time a bacterium divides, its DNA also divided, so each new bacterium is genetically identical to its predecessor. If in the process this will not happen any mutations — which can be according to the concept and functions of a survival mechanism. These mutations allow the bacteria, for example, to develop resistance to antibiotics that are trying to destroy them. On the other hand, some mutations are fatal to the organism or do not allow him to be born. And while it may seem that the choice inherent to cloning can circumvent these potential genetic disadvantages, scientists have found that it is not necessary.

What do the experts say?

Although Dolly the sheep is the most famous animal ever cloned with the help of science, it is obviously not the only one in its kind: scientists have cloned mice, cats and several types of livestock in addition to sheep. Cloning cows in recent years has provided scientists with an understanding of why they did not get everything: starting with problems during implantation and ending with the aforementioned mutations, which lead to the death of offspring. Harris Lewin, Professor, Department of evolution and ecology, University of California at Davis, and its scientists published work on the implications of cloning for gene expression in the journal proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2016. In the press release of the study, Levin said that the results were invaluable to the improvement of cloning techniques of animals, but their discovery “also stressed the need for strict prohibition of human cloning for any purpose”.

The creation of entire mammals with reproductive cloning was a difficult process both practically and ethically, says the lawyer and ethics Stanford University’s Hank Greely:

“I think no one understood how difficult it would be to clone some species and easy — to others. Cats are easy, dogs are hard, mouse is easy, rats — hard, humans and other primates is very difficult.”

The cloning of human cells can be, in contrast, is much more applicable for people. Scientists call this process “therapeutic” cloning, that is cloning for medical and therapeutic purposes, and distinguish it from traditional cloning, which has reproductive implications. In 2014, scientists created human stem cells by the same technique of cloning, which created Dolly the sheep. As the stem cells can be made to be any cells of the body, in the treatment of diseases they will be most helpful — especially genetic diseases or when the patient requires a transplant of another organ donor which is often unavailable. This potential application is on the way: earlier this year a woman from Japan, who suffers from age-related macular degeneration, treated with induced pluripotent stem cells created from her own skin and transplanted it on the retina. Her vision has improved.

Most interested people agree that we are approaching the milestone of a successful human cloning. 30% of respondents say that the first human cloned by 2020. What do you think?

How close are we to the first successful human cloning?

Ilya Hel