On Friday, May 3, China launched the Chang'e-6 mission to return to the far side of the Moon. The launch took place from the Wenchang Cosmodrome in southern China at 5:27 am. This event is especially noteworthy since the mission of the spacecraft is to collect soil from the far side of the Moon and send it to Earth. This will happen for the first time in the history of mankind, since during previous missions soil was mined exclusively from the visible (near) side of the satellite. According to scientists, there are good reasons to study the soil on the far side of the Moon, since it is very different from the previously mined regolith.

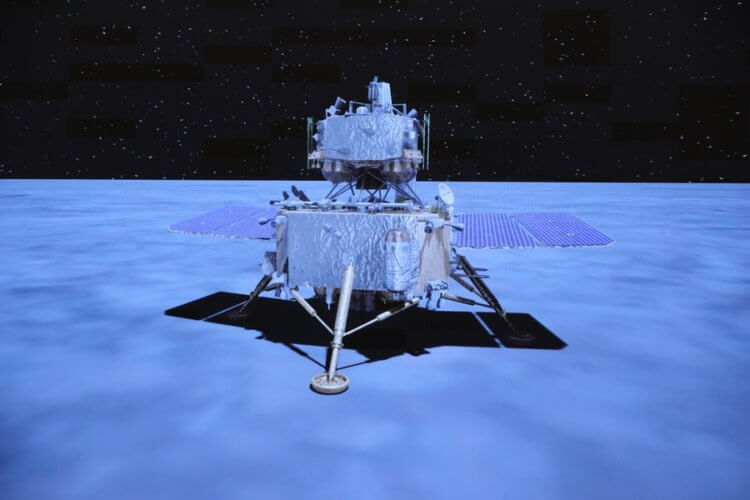

China launched the Chang'e-6 mission to deliver soil from the far side of the Moon to Earth. Photo source: euronews.com

The far side of the Moon is poorly understood

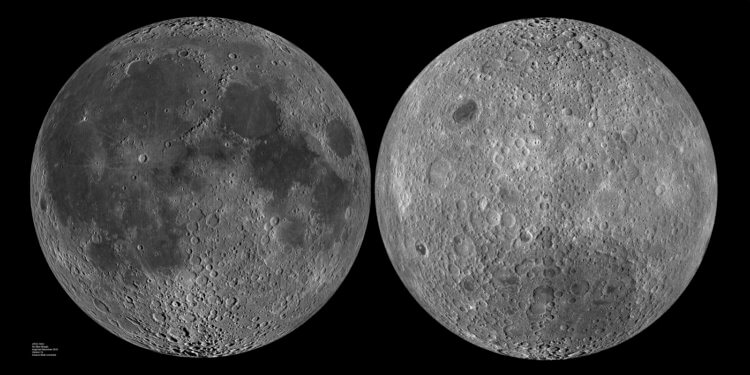

The Moon is not only “tied” to the Earth, but also synchronized with our planet. It makes one revolution around its axis in the same time it takes it to fly around the planet. As a result, we always see only one side of it.

Of course, the visible, or near, side of the natural satellite has been studied much better than the opposite. All lunar missions, from NASA's Apollo to China's Chang'e 4, have been aimed at this part of the Moon. This is partly due to the fact that sending landers to the back of the satellite is a rather problematic task.

In particular, there are difficulties with communication with the Earth. However, to solve this problem, China previously launched the Queqiao relay satellite. It is an orbital vehicle that receives a signal from the landing modules and transmits it to Earth. In addition, before the current mission, China launched a second repeater, Queqiao-2.

The far side of the Moon is very different from the near side, but scientists don’t know why. Photo source: universemagazine.com

Why is it important to get soil from the far side of the Moon

Scientists first began to explore lunar soil after the Apollo missions back in the 60s and 70s. Then there were more missions to deliver regolith. But, it would seem, what difference does it make from which part of the Moon it was delivered? However, according to scientists, there is a difference. The fact is that the far side of the natural satellite is very different from the near side.

For example, on the near side of the satellite there are large basalt plains, which are called seas. They occupy about a third of the surface. On the reverse side, their share does not exceed 1% of the entire surface. Scientists do not yet know what causes such differences. It is quite possible that studying the soil will help find the answer to this question.

What is known about the Chang'e-6 mission

The Chang'e-6 mission includes four separate vehicles – a lunar orbiter, a landing module, a vehicle for taking off from the Moon and a return module to Earth. If the mission is successful, the lander will land inside the Apollo crater, as reported by LiveScince. This crater is part of the South Pole-Aitken Basin (SPA), one of the largest impact craters in the Solar System.

The landing module must collect 2 kg of lunar soil. Image source: russian.news.cn

This region contains information not only about the early history of the Moon, but also about how and when massive objects bombarded the Moon and Earth billions of years ago. Therefore, most likely, by studying this part of the satellite, scientists will be able to solve its main mystery.

During the Chang'e-6 mission, the device must collect 2 kilograms of lunar soil. One part will be scraped off from the surface, and the other from a drilled hole 2 meters deep. The soil will first be delivered to the orbital vehicle, and then a special module will deliver it to Earth.

As a result, soil samples will arrive on our planet. In total, the mission will last 53 days. Let us recall that earlier, as part of the Chinese mission “Chang’e-5”, samples from the surface of the Moon were already delivered to Earth. Since there is already experience in such missions, Chang'e-6 has a high chance of success.

Don't forget to subscribe to our Zen and Telegram channels so as not to miss the most interesting and incredible scientific discoveries!

Finally, we note that the success of the previous mission made China the third country that was able to deliver soil samples from the Moon. Before China, the United States and the Soviet Union did this. Moreover, most of the soil was mined by Apollo astronauts – they delivered 382 kg between 1969 and 1972.