In the 30s and 40s of the last century, Malcolm Campbell was no less famous than, for example, kings, presidents and ministers of major powers. The reason is that this man was literally obsessed with speed and set world records on land and water. But the most interesting thing is that the descendants of Malcolm Campbell followed in his footsteps and continued to set new records. Donald Campbell, one of his sons, ended his life tragically while trying to overcome his own achievement on the water at Lake Coniston in 1967. The pilot's body was not found and recovered from the water until more than 30 years later.

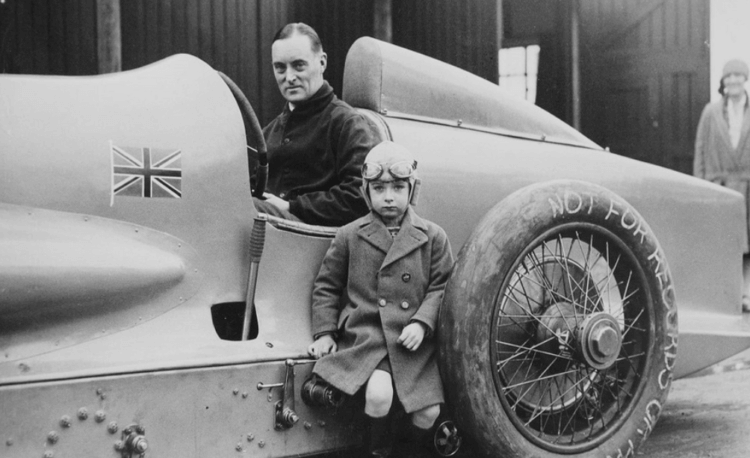

The Bluebird car in which Malcolm Campbell set his last speed record. Photo source: radiolemans.co

Contents

- 1 “Blue Bird” by Malcolm Campbell

- 2 Records Malcolm Campbell's speed in the 20s

- 3 New records and the latest achievements of the driver

- 4 Blue Bird V with a secret Rolls-Royce R engine

- 5 Speed record Malcolm Campbell on water

- 6 Speed achievements on water by Donald Campbell

- 7 Records of Donald Campbell on land

- 8 Death of Donald Campbell

“Blue Bird” Malcolm Campbell

Malcolm Campbell was born on March 11, 1885 in Britain, the city of Chislehurst. While studying in Germany, he became actively interested in motorcycles and motorcycle racing. Therefore, a few years after returning to England, he devoted himself entirely to motorsports. Campbell won three London to Lands End Trials motorcycle races between 1906 and 1908.

However, already in 1910 he switched to car racing, and called his first racing car “Blue Bird”. From then on, he and his descendants gave this name to all their racing cars and water gliders. At the same time, they painted the cars themselves blue. Malcolm Campbell came up with this name under the impression of Maurice Maeterlinck’s play of the same name “The Blue Bird,” which he saw in the theater.

At the outbreak of the First World War, Malcolm Campbell was drafted as a military motorcyclist and took part in the Battle of Mons in August 1914. He was then transferred to the Royal Flying Corps. Even before the war, he had some experience of flying on various aircraft, including one he created with his own hands.

Malcolm Campbell in a racing car. Photo source: rdrc.ru

Speed records of Malcolm Campbell in the 20s

In the 1920s, Malcolm Campbell purchased a Sunbeam sports car, which allowed him to accelerate to a record speed of 226 kilometers per hour. After repairs, maintenance and repainting, the Blue Bird went to the island of Fanoe in Denmark and was able to reach an even higher speed of 234 kilometers per hour. However, this record did not receive international recognition.

But that didn't stop Campbell. After tuning the car and several unsuccessful attempts, it accelerated to 235.22 kilometers per hour, breaking the official record previously set by a Fiat car in France. This time his achievement was recorded and generally recognized.

When Malcolm Campbell heard rumors that John Godfrey Parry Thomas was going to break his record, he made another race and was able to accelerate his car to 242 kilometers per hour , becoming the first driver to break 150 mph. In honor of this event, he created several Sunbeam cars with a 350-horsepower 18.3-liter engine. Two of them have survived to this day.

Racer Henry Seagrave (left). Photo source: techinsider.ru

However, the record did not last long. The very next year, Henry Seagrave surpassed the maximum speed in a car with a thousand horsepower engine. Of course, this pushed Malcolm Campbell to new achievements. Over the next ten years, he prepared for a new record.

At the beginning of 27, the Napier-Campbell Blue Bird was created for this, that is, the third version of the Blue Bird with a twelve-cylinder Napier Lion engine with a power of about 450 horsepower naturally aspirated and with a volume of 22.3 liters. By the way, the Supermarine S.5 seaplane was equipped with a similar engine.

In this car, Malcolm Campbell accelerated to 314 kilometers per hour. However, Henry Seagrave's racer soon reached a speed of 320 kilometers per hour in a Sunbeam car with a 1000-horsepower engine. Then Campbell rebuilt his car and installed a new, more powerful engine, on which he accelerated to 333 km/h in February 28. But this record remained unbroken for about two months.

Malcolm Campbell in one of his Blue Bird racing cars. Photo source: avto.review

In 29, the racer decided to find a more suitable route for new achievements, since the sandy beach on which previous records were set was, in his opinion, not predictable enough. As a result, he chose the bottom of the dry lake Vernoikpan as the route.

New records and the latest achievements of the racer

On his birthday, when Malcolm Campbell turned 44, he learned that his record had been broken by Henry Seagrave, who accelerated to 372.47 km/h in a Golden Arrow. On the new African track, Blue Bird could not achieve the same result. True, he set world records at distances of five and ten miles, driving them at a speed of 341 km/h.

However, Henry Seagrave, Campbell's main rival, soon died. The tragedy occurred in the summer of 1930 while trying to set another record on the water, while Campbell himself was working to overcome the record on land in Africa. Despite the rivalry between the two drivers, Campbell took the death of his colleague hard.

One of the versions of the Blue Bird car that Malcolm Campbell drove at 30 -s years. Photo source: www.reddit.com

Also concerned that the new record might be broken by the Americans (Henry Seagrave was British), Malcolm Campbell accelerated to 396 km/h, and a year later reached a speed of 404 km/h. These events received a great response in the press, and the driver himself was knighted and became Sir Malcolm Campbell.

For new records, Malcolm Campbell used the 1931 Campbell-Napier-Railton Blue Bird IV, which had an updated Napier Lion VIID engine that developed 1,350 horsepower. It was the first supercharged engine ever used in such a car. In addition, an aerodynamic stabilizer was installed on the car for the first time.

Blue Bird V with a secret Rolls-Royce R engine

In '33, Campbell needed a new powerful engine, so he applied to the Air Ministry and received permission to use the secret Rolls-Royce R engine, which was installed on Supermarine S.6 seaplanes. Its power was 2300 hp, and its engine capacity was 36.7 liters. The engine ran on fuel specially developed for it in the form of a mixture of benzene, methanol, acetone and tetraethyl lead. The body shape of the new car was also greatly changed this time.

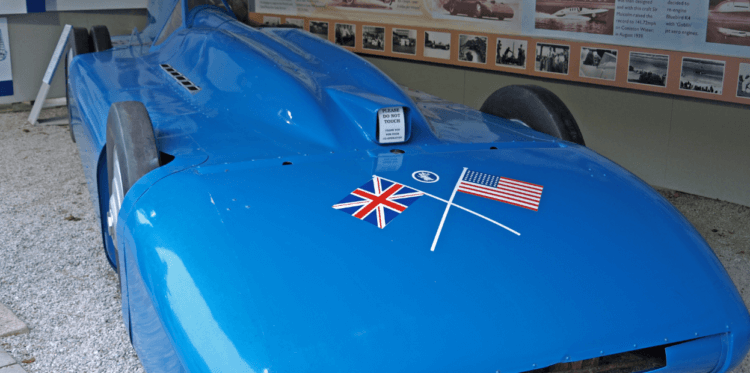

Bird V car. Photo source: Wikipedia

The first record for this car, set in February 1933, was 438 km/h. However, during the race, a problem was identified – slipping of the rear wheels, which led to a loss of speed. Two years later, after refining the design, Campbell improved his performance to 445.5 kilometers per hour. And in September 1935, he accelerated his car to 489 km/h. This was his last record in existence.

Malcolm Campbell's speed record on water

Having achieved considerable success on land, the racer decided to achieve similar success on water and surpass the Americans. The Blue Bird K3 glider was built on the same Rolls-Royce R engine, weighing more than 700 kg. The length of the vessel was 7 meters and the width was 2.9 meters. This made it possible to provide the required displacement of 2243 kg.

The glider had a hull with one keel and a flat bottom. The hull was made of plywood, and in case of a crash, the designers provided several tens of thousands of ping-pong balls sewn into bags. Such floats provided a reserve of buoyancy.

The Blue Bird K4 sports boat that set the world speed record. Photo source: Wikipedia

However, Campbell was not satisfied with his speed rating of 130 miles per hour, as a result of which he began building a new glider. Unlike the previous vehicle, the new boat had a three-point hydrodynamic design and three keels. At maximum speed, the boat came into contact with the water at only 3 points. In this way, hydrodynamic resistance was reduced.

Under the bottom of the glider, a lifting force arose, which sought to lift the boat from the water. However, in the event of separation, the flight became chaotic and was fraught with an accident.

On the new Blue Bird K4 planer, Malcolm Campbell achieved his goal of setting an absolute record, accelerating to 141 mph on Lake Coniston. This happened in the summer of 1939. This was the end of his racing career. He lived another 9 years and died in 1948 at the age of 64 from illnesses.

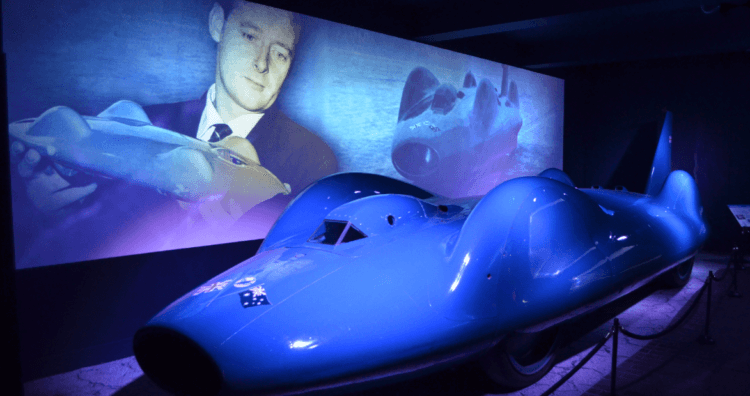

Donald Campbell, son of Malcolm Campbell. Photo source: rus.team

Achieving speed on water by Donald Campbell

Against his father's wishes, Donald Campbell followed in his footsteps. In the summer of 1949, on Malcolm Campbell's boat Blue Bird K4, he decided to break the record set by his father. True, he failed to do this; he only came close to the cherished speed. But he didn’t stop there.

After modifying the Bluebird K4, in September 1951, Campbell Jr. managed to accelerate his seaplane to 270 km/h. True, this record led to the destruction of the boat. In addition, the very next year the American Stanley Sayres raised the record to 286 km/h.

It must be said that at this time another British racer, John Cobb, was testing his Crusader jet seaplane. However, in 1952 he died during testing. Campbell Jr. was upset by this event, but decided to return the British championship bar, and built a new seaplane, the Bluebird K7, powered by a jet engine. On this boat he was able to break 7 world records from 1955 to 1964 inclusive. The latest record was 444.71 km/h.

Donald Campbell's Bluebird K7 sports boat. Photo source: ginacampbell.co.uk

Donald Campbell's land records

Having achieved success on the water, in 1956 Donald Campbell began building a new car. He attracted several companies to his project, such as Dunlop, BP, Lucas Automotive, Smiths Industries, Rubery Owen and others. As a result, by the spring of 1960, the Bluebird-Proteus CN7 machine appeared. The tests took place on the Bonneville salt flats.

During one of the races, the driver lost control and crashed at a speed of 360 miles per hour. However, thanks to the special design of the machine, he did not die, although he was hospitalized with a skull injury. Rubery Owen took on the task of restoring the car and successfully completed the task.

Donald Campbell Bluebird-Proteus CN7 sports car

After a long selection of routes, Donald Campbell decided to take advantage of a flat area on one of Australia's dry lakes. As a result, by the end of '62, the restored Bluebird CN7 was sent to Australia. However, the race did not take place due to the weather.

In the spring of 1964, Donald Campbell again went to Australia, but due to the fact that the track was still wet, it was only in mid-July that he made a race and set a speed record of 648.73 km/h.

The death of Donald Campbell

Donald Campbell set himself a goal – to set a speed record on water and on land in one year. The last time he succeeded was in 1964. To achieve his goal, he began building a new seaplane, the Blue Bird K7, with which he planned to set a supersonic speed record.

The glider was quite compact, and equipped with Bristol Siddeley BS.605 rocket jet engines, which were used in military aircraft. In the spring of '66, Campbell began to overcome the new record, but due to bad weather it was not possible to carry out tests – a lot of debris got into the air intakes and into the engine.

In December, when the weather improved, he made several races with speed above 400 km/h, but he was not satisfied with this result. The boat was modified, and

new test runs began on January 4, 1967. In the first of them, Campbell drove at a speed of about 459 km/h.

During the second race, the racer reached a speed of 480 km/h, but due to changing weather or waves, the boat came off the water and crashed. Rescuers quickly arrived at the crash site, but were unable to find either the body of the racer or the boat itself. Only a mangled float remained on the surface.

The Blue Bird K7 boat on which Donald Campbell died. Photo source: www.bbc.com

Only on March 8, 2001, it was possible to find and raise the deformed skeleton of the boat from the bottom of the lake, and two months later the remains of Donald Campbell himself were found. As a result, he was buried on September 12, 2001. The Blue Bird K7 boat was restored from the wreckage and is currently in the museum.

Be sure to subscribe to our Zen and Telegram channels. This way you will always be aware of new scientific discoveries!

Subsequently, Gina Campbell, daughter of Donald Campbell, broke the women's water record. In 1984, she reached speeds of 122.86 mph on the Agfa Bluebird. And Campbell's nephew set a speed record in an electric car. Finally, we note that the pursuit of speed continues – athletes set new records on land and water, although not as often as it was half a century ago. For example, in 1997, a speed record of 1227 kilometers per hour was set on earth, which has not been broken to this day.