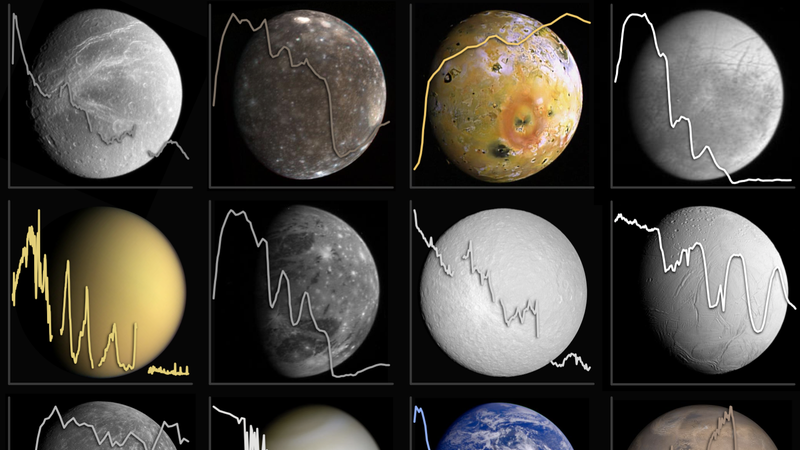

The planetsGraphic: Jack Madden, Carl Sagan Institute

The planetsGraphic: Jack Madden, Carl Sagan Institute

By searching for the telltale, periodic dimming of light from distant stars, astronomers can spot orbiting exoplanets tens to hundreds of light-years away. But how do they know what these bodies look like? Perhaps they first try to imagine how the planets in our own Solar System might appear to a faraway alien world.

A pair of scientists has released a detailed catalog of the colors, brightness, and spectral lines of the bodies in our Solar System. They hope to use the catalog as a comparison, so when they spot the blip of an exoplanet, they’ll have a better idea of how it actually looks.

“This is what an alien observer would see if they looked at our Solar System,” study coauthor Lisa Kaltenegger, director of the Carl Sagan Institute at Cornell, told Gizmodo. With this data, astronomers might guess whether an exoplanet is Earth-like, Mars-like, Jupiter-like, or something else entirely.

Scientists have discovered thousands of exoplanets, with thousands more to come, thanks to the Kepler/K2 missions and the just-launched TESS mission. With more exoplanets comes more data on their mass and temperature, and sometimes even spectra, the light signature of the elements in the planets’ atmospheres. Soon, missions like the upcoming Extremely Large Telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope could return spectra from lots of these planets.

All of that incoming data motivated Kaltenegger and coauthor Jack Madden to make this catalog of colors, spectra, and albedos, or how much the planet reflects starlight. They analyzed published data to create fingerprints for 19 objects in our Solar System, including all eight planets, the dwarf planets Pluto and Ceres, and nine moons. Their works is published in the journal Astrobiology.

The full catalogGraphic: Jack Madden

“It’s smart to leverage everything we know about our own Solar System,” said Kaltenegger. “We have gas giants, the rocky planets, and all these interesting moons. We basically made a reference fingerprint.”

Others are excited to have a tool like this.

“It’s enormously important to use the Solar System as ground truth for exoplanet studies,” Laura Kreidberg, a Harvard astronomer who was not involved in the new work, told Gizmodo. “Even with the vast sample of exoplanets at our disposal, we’ll never be able to explore them in the same exquisite detail as we have for the Solar System.” Kreidberg felt the paper was a “stepping stone for understanding planets around other stars.”

“It’s incredibly information rich—I’ve been poring over the plots and keep seeing more and more interesting similarities and differences,” Jessie Christiansen, astrophysicist at Caltech, told Gizmodo. “These kinds of analyses are essential for designing the future flagship NASA missions that will study these worlds.”

Both Christiansen and Kreidberg noted that there are important places where incomplete data may make two vastly different planets look the same. For example, the colors of planets with liquid on their surface and bone-dry planets look similar. That means next-generation missions need to take things like this into account. “The difference between a tropical, wet oasis and a desolate, desiccated rock is huge when you’re looking for habitable planet,” said Christiansen.

Kaltenegger told Gizmodo she would like to update the catalog to include more moons and cooler objects. But this data will be important for both planning future telescope missions and characterizing exoplanets.

“Once we get the light that tells us about the atmosphere or surface of these worlds, what do you want to compare it to? The easy thing is to compare it to a wide, diverse set of other worlds,” she said. “We have one by looking at the moons and planets and dwarf planets.”

[Astrobiology]