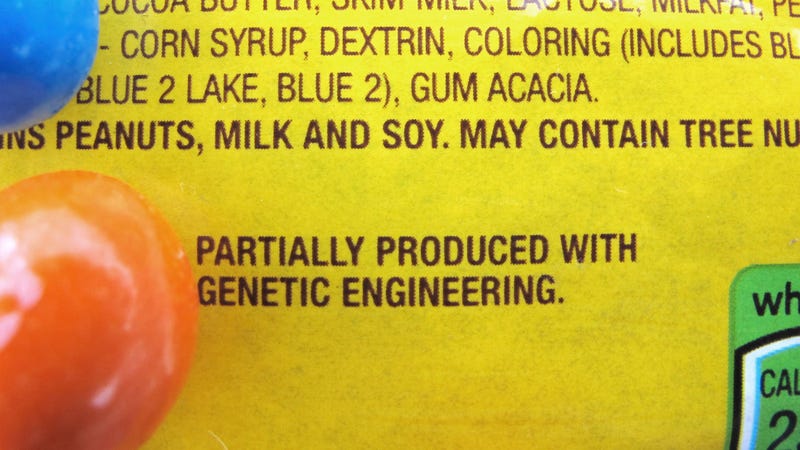

An example of the labeling used on some products after Vermont’s GMO labeling law passed in 2014.Image: Damian Dovarganes (AP)

An example of the labeling used on some products after Vermont’s GMO labeling law passed in 2014.Image: Damian Dovarganes (AP)

A new study seems to provide an interesting wrinkle in the debate over whether foods containing genetically engineered ingredients (otherwise known as either GE or GMO foods) should be labeled as such. It turns out that people living in Vermont actually became less distrustful of GMOs following a temporary state law that mandated a simple labeling system, especially when compared to people living in the rest of the country, according to a paper published Wednesday in Science Advances.

The findings are especially relevant in light of an upcoming federal law that will standardize how products containing GMOs should be labeled.

The majority of scientific research has shown GMO foods aren’t any less safe than food traditionally produced. But labeling advocates have nonetheless demanded these foods be identifiable, arguing that it would let customers make an informed choice. Many public health experts, however, have argued that labeling foods as GMOs will only encourage people to mistakenly believe these foods are somehow riskier to eat.

Amidst this contentious fight, Vermont passed a labeling law in 2014. It required that foods disclose whether they were produced or partially produced using genetic engineering. And on July 1, 2016, Vermont became the first state to have such a law come into effect. But less than a month later, former President Obama signed a bill that would dictate how GMOs should be labeled nationwide. The new law provided the federal government, and in particular, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), a two-year grace period to create labeling regulations. It also immediately suspended any state labeling laws on the books or already enacted, including Vermont’s.

But according to the new study’s lead author, Jane Kolodinsky, foods sold in the state continued to feature GMO labeling long after Obama’s decree, including to the present day. That provided Kolodinsky, an applied economist at the University of Vermont who has studied people’s attitudes toward GMOs for nearly two decades, an ample opportunity to pull off a natural experiment of sorts.

She and her co-author collected data from two separate sets of surveys of people in Vermont and across the country about GMO attitudes. The surveys collectively interviewed nearly 8,000 people from March 2014 to March 2017. People’s feelings toward GMOs were measured on a one-to-five scale, with five representing strong negative feelings. The questions were worded slightly differently between the two sets of surveys, though. The national survey, conducted online, asked people to rate how concerned they were about the health risks of certain foods, including GMOs; the Vermont surveys, conducted via the phone, instead asked people to rate how supportive they were of including GMOs in the food supply.

Based on the surveys, people in Vermont were already more anxious about GMOs before the 2016 law was enacted, compared to the rest of the country. But after the labels began appearing on foods, people’s altitudes relaxed in the state, from an average rating of 3.36 down to 3.077. Nationwide, meanwhile, people’s attitudes toward GMOs slightly grew more hostile (though, overall, the average rating also hovered around the low threes). Relative to the rest of the county, the researchers found opposition to GMOs had dropped 19 percent since the law had been passed in Vermont.

The study is especially valuable, Kolodinsky says, because it’s the first to rely on real-world data in the US. And the decrease in opposition is all the more interesting because GMO attitudes have steadily become more negative in Vermont and in the US overall for years. Though the study can’t answer why people became less afraid of GMOs, the authors point to previous research suggesting that labels give consumers a sense of control.

However, there are some limitations to the study. For one, there’s no telling just how often people surveyed in Vermont actually got to see GMO labeling on their products. Some companies, including General Mills, also decided to label their GMO products regardless of where they were sold in anticipation of the Vermont law, so some people outside of Vermont undoubtedly saw this kind of labeling as well.

But given the drastic differences seen between the two data sets, Kolodinsky says, it’s likely that Vermont residents did see lots more labeled products than anyone else would have, and that these labels helped set their mind at ease. The difference in attitude was seen even when you accounted for states next to Vermont, which might have had GMO labeled foods produced regionally on their store shelves.

Still, while the findings seem to dispel some concerns about the labeling laws, it’s hard to say what effect the upcoming federal labeling rules will have. Unlike Vermont’s law, the proposed labeling regulations unveiled by the USDA this May could be more complex for customers to wrap their heads around.

Certain ingredients previously recognized as genetically engineered might become exempt from labeling, such as highly refined sugars and oils made from GE corn or soybean, which has angered labeling advocates (the argument being that these processed products have no genetic material left behind from the original GE crops used to make them). The USDA has also proposed changing the words used to describe genetic engineering from GE or GMO to “bio-engineered,” or BE, which might confuse people accustomed to the old terms, Kolodinsky explained.

Companies will also have the option of having customers scan their product’s QR code through a smartphone to find out about their GE ingredients. But the USDA’s own commissioned research has suggested that customers are unlikely to know about these codes and how to use them.

“It seems that the most simple labeling scheme—that is providing the disclosure ‘produced or partially produced using genetic engineering’—would be the least complicated way to inform consumers about how their food is produced,” Kolodinsky said.

The USDA’s proposed rules are subject to public comment until July 3 and are expected to be finalized later this summer.

[Science Advances]