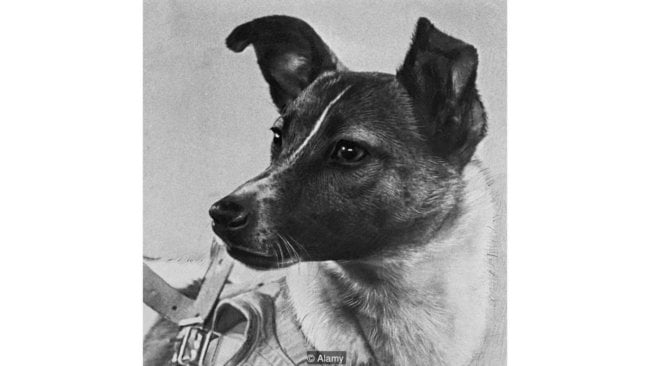

The engineers, imprisoned Husky in a narrow windowless space capsule, the “Sputnik 2” November 3, 1957, knew that seeing her one last time. Following the success of “Sputnik-1” on 4 October, Nikita Khrushchev ordered to send into space a dog within a month. Yes, before the appearance of cosmonauts and astronauts in ink unknown went brave stray dogs. Their descendants were where no one dared to expect. How to return of the dogs themselves, no one knew, and not planned.

“It was a mission at one end,” says Doug Millard, curator of space at the London science Museum. “It was in the midst of the cold war, and the case was serious because the seething struggle between the superpowers”.

As soon as the Husky was in orbit, the world learned that during the week she will live in total comfort, with plenty of food and water, before safely leave. In 2002, it turned out that the dog only lasted seven hours before you die from panic and exhaustion.

But for the Soviet Union, this mission became another propaganda victory, and Laika is a national hero. Running a large capsule with a size of 113 pounds with live animals on Board, the Russians were ahead of the rest — and especially Americans — in the space and missile technologies.

“On the one hand, we can say that the effect was as great as in the case with the first “Sputnik,” says Millard. “It certainly has had a major impact on the United States — so serious that it became obvious that the Soviets could put a nuclear warhead on a missile and deliver it in the United States.”

The Soviet Union flew into space with dogs from the first days of its space program, while the engineers tried to rebuild the captured V2 of Wernher von Braun. The first flight was suborbital, dogs were sent into the atmosphere and returned to Earth. Unlike the Huskies, most dogs survived.

While Americans prefer to experiment with monkeys and chimpanzees, the Soviet scientists chose dogs because they were easier to train, they were many people tied to them (and Vice versa). All dogs were purebred females.

“There remained the question of how to catch them,” says Millard. “Just imagine how the participants of the space program roam the streets of Moscow in search of suitable dogs and convince those to go with them.”

“They needed a healthy dog, so they couldn’t dehumanize them. They were given a name, their own kennel and a well-fed dog should have been happy and grateful to the people who treat her”.

Dogs passed thorough medical testing and extensive training programs that they were comfortable in space suits and in close capsules. Most flew in pairs, allowing scientists to compare data of the two animals.

In just three years, the Soviet space dog made the story. August 19, 1960, Belka and Strelka were launched into orbit together with two rats, a rabbit, fruit flies and plants.

“The flight went well, and all the medical data received from their space suits, was right,” said VIX Southgate, currently working on a book about space dogs. “But at the time of achieving orbit, none of them moved”.

Then, on the fourth orbit, the Squirrel started to feel sick. “That shook them both,” says Southgate. “From the video recorded on Board, you can see how dogs are barking and moving, but medical data has shown that they are calm and not particularly tense”.

After seventeen orbits, ground controllers activated the retro rockets and lowered the dogs on the Ground. When the capsule was opened, Belka and Strelka were happy and safe. After a few hours they became known to the whole world. Dogs appeared on the covers of Newspapers, talked about them on television.

“Their fame has spread internationally, stamps, postcards, they were absolutely everywhere,” says Southgate. “It was phenomenal”.

And then the story took a completely different turn.

In June 1961, two months after Yuri Gagarin became the first man to orbit the Earth, President John Kennedy and Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev held their first joint summit in Vienna. The meeting was heavy. But during the dinner, Jackie Kennedy began to talk with the Soviet leader about the space dogs.

“He mentioned that the Arrow was a puppy, and she said that he should send one of her puppies,” says the historian of the Presidential Pets Museum Andrew Hager. “A few weeks in the White house was one of the puppies from a small Russian passport”.

After the FBI checked the dog for bugs, Nothing settled in the first family. Although the US President was allergic to dogs, the Fluff of her time with children and friends — really friends — with another dog of the White house, Charlie. The dog pair of puppies appeared. “It was a wonderful novel during the cold war,” says Hager.

But the gift of the Feather, in his opinion, was of great diplomatic significance, and even helped to prevent a Third world war. “It was more than just a gift; I think the Feather has a historical significance,” says Hager. “Kennedy and Khrushchev supported this feedback and gifts were exchanged in that period.”

“And that’s really helped them to cool, when it came to the Cuban missile crisis a year later,” says Hager. “I think that Fluff has become part of the thought process that took the leaders through the missile crisis, and the reason that caused Kennedy to think, not to listen to the vultures of the White house and not bomb Moscow.”

Two puppies of Fluff was given to the American children who wrote to Jackie Kennedy with a request to care for the dogs. When Kennedy was killed in 1963, a Feather handed over to the gardener of the White house, and later she was again delivered of puppies.

Hager tried to trace the descendants of a Feather, but still couldn’t. “Perhaps in the United States are still living descendants of Russian dogs cosmonauts,” he says.

As for the space dogs, after the first successful flights of the astronauts, the program was closed. But Millard believes that these pioneers of space flight deserve more than a mark on the fields of cosmic history.

“I think that neither they nor the American flying chimp has not yet received the recognition they deserve,” says Millard. “The way to the stars for humans was paved with dogs and monkeys”.

The story of the offspring mongrels who paved the way into space

Ilya Hel