If you thought all limited to what we have found over the cosmic horizon, get ready to change your mind.

“It’s hard to build models of inflation that don’t lead to a multiverse. It’s not impossible, so I am sure the need for additional research. But most models of inflation do lead to a multiverse, and evidence for inflation will be pushing us in the direction of the serious adoption of [multiple universes],” said one day, Alan Guth, American physicist and cosmologist who first proposed the idea of inflation or cosmic expansion.

Imagine that the universe we observe, from end to end, is just a drop in the cosmic ocean. Which is beyond what we can see, there is more space, more galaxies, most of all, countless billions of light years further than we are ever able to reach. And how vast can be the universe, as countless can be the number of universes similar to it — more and some older, some younger and less — scattered throughout the space-time. And as fast as these universes are expanding, space-time containing them, expanding even faster, takes them further away from each other and ensures that no two universes will never meet. Like science fiction? This is the scientific idea of the multiverse theory or multiple universes. But if the scientific view that we are adopting today, correct, this idea is not only appropriate, but inevitable consequence of our fundamental laws, says physicist Ethan Siegel.

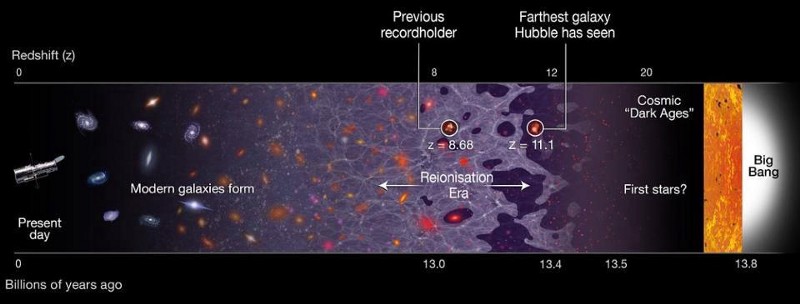

The idea of multiple universes is rooted in physics, needed to describe the Universe that we see and in which you dwell today. Everywhere in the sky we see stars and galaxies, grouped in a large cosmic web. But the farther into space we look, the further back in time we go. The farther the galaxy, so they are younger and thus less developed. In their stars less heavy elements, they seem to be less, since there have been fewer mergers, more spirals and fewer ellipses (because the latter takes time), and so on. If we move to the limits of the visible, we find the very first stars in the Universe, and behind them — the realm of darkness, where there is only one light: the afterglow of the Big Bang.

The Big Bang — which happened 13.8 billion years ago, was not the beginning of space and time but rather the beginning of our observable Universe. This was the era known as cosmic inflation, when space itself expanded exponentially, filled with the energy inherent in the fabric of space-time. Cosmic inflation is itself an example of the theory that came in and replaced the one that came before it:

- It is consistent with all the successes of the Big Bang theory and covered all of modern cosmology.

- She explained a number of issues that could not explain the Big Bang, including why the universe was everywhere the same temperature, why it is spatially flat, and why no high-energy relics like magnetic monopoles.

- And she has made many new predictions that could test the observation, the majority of which were confirmed.

But there was one consequence, which is predicted by the theory of inflation. We don’t know whether we can confirm it or not: multiple universes.

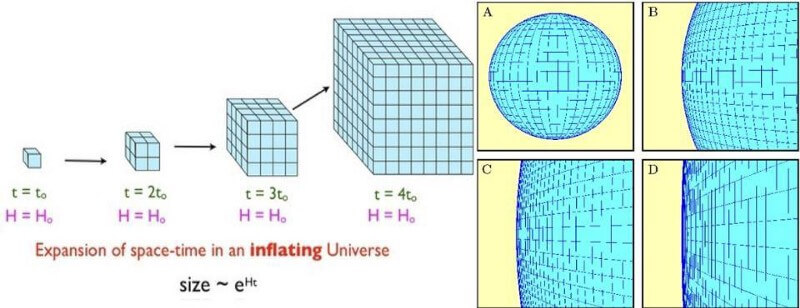

Inflation leads to an exponential expansion of space that can very quickly lead to the fact that any pre-existing curved space will appear to be flat

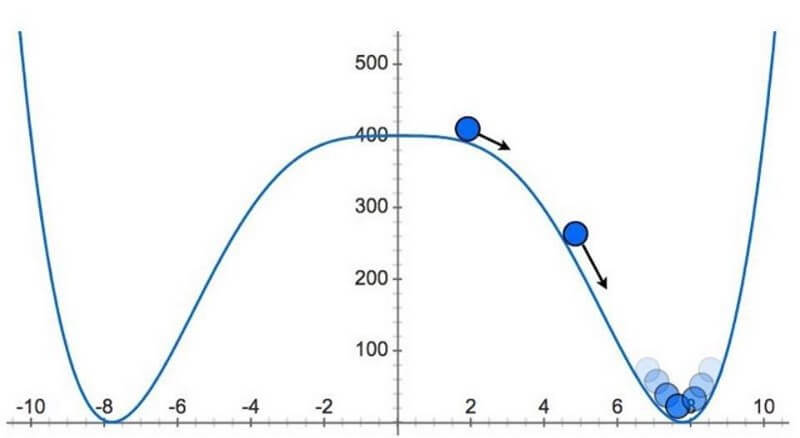

Inflation leads to the fact that space is expanding exponentially. That has taken anything that existed before the Big Bang, and it becomes much, much, much more than it was. Yet it suits us: it explains how we got a uniform and a vast Universe. When inflation ends, the universe is filled with matter and radiation, which we observe as the hot Big Bang. And here it gets weird. That inflation ended, no matter what the quantum field is responsible for it, she needs to move from unstable high-energy state to low-energy and stable. This transition and the “rolling” down in the valley — that causes inflation to end and causes a Large Explosion.

But regardless of which field is responsible for inflation, as in all other areas of physics, it must be inherently quantum field. Like all quantum fields, it is described by a wave function with a probability of recession of a wave over time. If the magnitude of the field will slowly slide into the valley, quantum scattering wave function will be faster rolling, meaning that it is possible — even likely — inflation will gradually lead to the Big Bang.

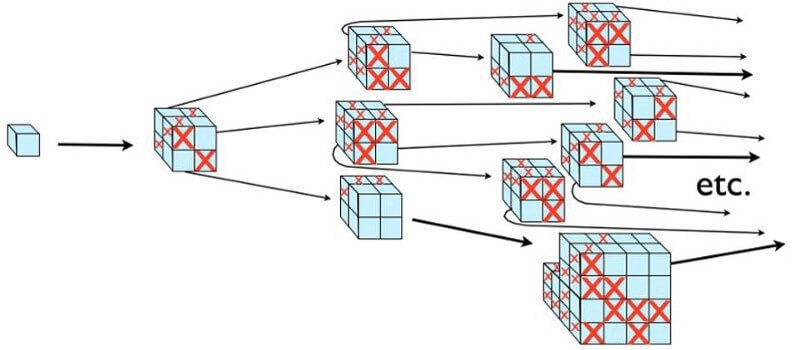

If inflation was a quantum field, the value field will scatter over time, and different area of space will take a different realization of the value of the field. In many regions the value of the field will get to the bottom of the valley, ending inflation, but in many other inflation will continue indefinitely in the future

Since space is expanding at an exponential rate during inflation, which means that over time creates an exponentially greater number of regions of space. In certain areas, inflation will end: where the field rolls down to the valley. But in other inflation will continue, creating more and more space around each area where the end of inflation. The rate of inflation much faster than even the maximum rate of expansion of the filled with matter and energy the Universe, so in the shortest time plots of inflation take over. According to the mechanisms that provide us with sufficient inflation to create the Universe which we see, our region of space where inflation has ended, surrounds much more than other regions where inflation continues or is ended immediately.

Inflation continues indefinitely, despite the parts where it ended

This is a phenomenon known as eternal inflation. Where the end of inflation, is born the Big Bang and the universe — like the one we observe — similar to our own. But where inflation does not end here, there are more of inflationary space, which gives rise to the other regions in which large explosion, separate from ours, and other regions in which inflation begins.

How big is our universe, it is only a small part of all that really is

This painting is huge universes, much larger than the meager part that we can see is constantly being created, like space, is a multiverse. It is important to understand that the multiverse is not a scientific theory in itself. It makes no predictions and observed phenomena, to which we can reach. No, the multiverse itself is a theoretical prediction that follows from the laws of physics that we have bred to date. Perhaps it is even inevitable consequence of these laws: if we take the inflationary Universe governed by quantum physics, we’ll get it.

Perhaps our understanding of this condition, what was before the Big Bang, is wrong, and that our ideas about inflation is completely wrong. In this case, the existence of multiple universes will not be the final result. But the prediction of eternal inflation contains countless numbers of pocket universes is a direct consequence of our best theories, if they are true.

What is the multiverse, in such a case? It can go beyond physics, and motivated to become the first physical “metaphysics” with which we have ever encountered. First we understand the boundaries of what can we learn from our universe. Until then, we can predict, but can not neither confirm, nor deny the fact that our universe is just one small part of a larger Kingdom: the multiverse.

Multiple universes do not just exist: we live in them

Ilya Hel