Image: CDC/Wikimedia Commons

Image: CDC/Wikimedia Commons

We consume all sorts of things before really knowing how they’re going to affect us, including probiotics and dietary supplements. But given how preliminary our understanding of our gut bacteria is, it’s very likely that some supplements can work in direct opposition of others. For instance, vitamin A might kill a bacteria hypothesized to promote childhood growth.

How supplements impact our microbiome is important, not so much for dodos taking fists full of pills to “stay healthy” as for folks suffering from malnutrition, especially in lower-income countries. The World Health Organization recommends high doses of vitamin A for children in places where vitamin A deficiency is common. But in a new study in mice, a vitamin A deficiency allowed one potentially beneficial species of gut bacteria to flourish. The unanticipated finding demonstrates that health professionals need to think about the gut microbiome when treating cases of malnutrition.

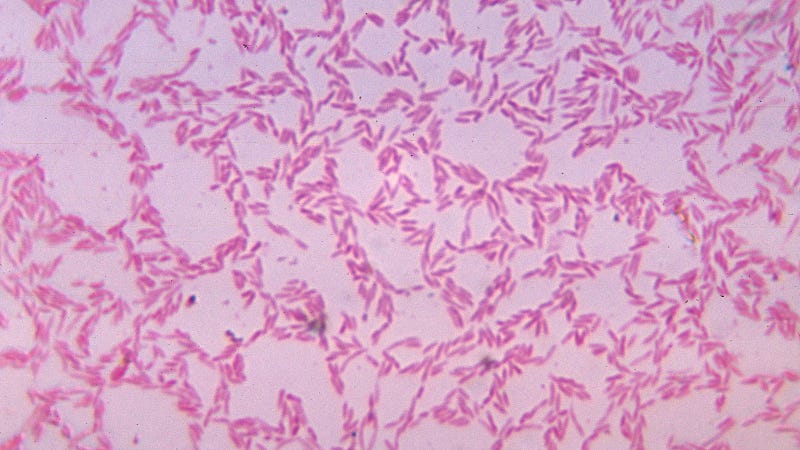

The gut microbiome is simply the slew of bacteria living inside our guts that play a role in our digestion. Problems with the gut microbiome might lead to illnesses like colitis, or Clostridium difficile. Some researchers think a more diverse microbiome—more species living inside of us—could be better for our health, or that certain bacteria could have key roles to play.

A team of American researchers has been studying the effects of diet on the microbiome for a while, by raising human bacterial colonies inside mice guts. In their latest experiments, they fed mice normal diets for two weeks, followed by some nutrient-specific diet for three weeks (they tested iron, folate, zinc, and vitamin A deficiencies), followed by a return to a normal diet.

Your Crappy American Diet Might Leave Your Gut Bacteria Stunted

Adopting a healthy lifestyle might not seem that hard on the outset. You ate a lot of cheeseburgers …

Read more

Analyzing the mice’s poop samples surprised the researchers, who published their results today in the journal Science Translational Medicine. Most surprisingly, less vitamin A meant more of one bacterium, called Bacteroides vulgatus, and vice versa. In a past study, scientists transplanted a healthy microbiome including this bacteria into malnourished mice, and it helped the mice grow more. As a result, researchers have tried to come up with ways to increase B. vulgatus abundance in malnourished patients. But that’s going to be hard to do if vitamin A simultaneously decreases the abundance of B. vulgatus.

This is just a single study and in mice, not humans, so it’s important not to oversell its results. “It’s hard to say that you can directly relate it [to humans], other than to say in the rodent model, alterations of vitamin A in the diet had an effect on the microbiota,” Boston University School of Medicine professor Michael Holick told Gizmodo. Holick studies Vitamin D and is looking at its effects on the microbiome, too, but pointed out that this whole area of study is still evolving. And the other nutrients studied had much less pronounced effects on B. vulgatus. Still, Holick felt the study lends evidence to the fact that specific nutrients might be playing a role in shaping the types of bacteria in our guts.

This doesn’t mean much for you—we already knew that you shouldn’t take too much vitamin A if you aren’t malnourished. But for those who are malnourished, or those trying to feed the malnourished, it’s an important element to consider. It’s certainly not a good idea to take a supplement that’s simultaneously working against the benefits of another one, after all.

[Science Translational Medicine]