Earth’s coral reefs are dying so quickly that some scientists say they’ll be gone by mid-century. But now, there’s a desperate attempt afoot to save these incredible organisms from extinction: in vitro fertilization.

After years of captive breeding, scientists are now reporting that lab-grown corals have reproduced in the wild for the first time. Specimens of Elkhorn—a highly endangered reef-building species that once blanketed vast swaths of the Caribbean seafloor—were reared from gametes collected in the wild, fertilized in vitro, and planted back out in the ocean. They have now reached sexual maturity.

For marine conservation biologists, this is a major achievement. But it’s a far cry from what’s needed to save coral reef ecosystems, which support a quarter of all marine species.

In 2010, researchers at SECORE international and several aquariums teamed up to develop techniques aimed at rearing large numbers of Elkhorn embryos in captivity. Unlike earlier “coral gardening” efforts, in which fragments of adult coral are collected, spawned asexually in nurseries, and then returned to their reef, the focus of SECORE’s effort has been on producing new genetic varieties of coral via sexual reproduction.

“SECORE developed a technique whereby male and female gametes are caught in the wild and fertilized in the laboratory to raise larger numbers of genetically unique corals,” SECORE director Dirk Petersen said in a statement. That genetic diversity is critical to weathering new environmental challenges.

Sponsored

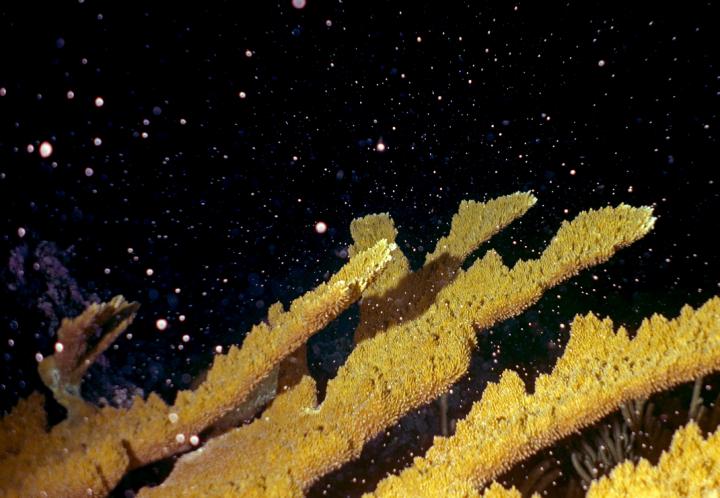

Elkhorn corals spawning by releasing gametes into the ocean at night. Via Benjamin Mueller – CARMABI

But injecting diversity into a reef is slow, tricky business. In the wild, Elkhorn corals only reproduce once a year, following the full moon in August. During the past several breeding cycles, SECORE biologists have set out nets to gently collect sperm and eggs as they’re released. The gametes are then brought to a lab and mixed in vitro to produce embryos. After a short period in a nursery, these embryos are settled out into a reef. Four years later, they’re ready to reproduce again.

While the team’s success is encouraging, SECORE is cognizant that lab-grown coral aren’t going to be performing any miracles. In the Caribbean, coral populations have declined an estimated 80 percent over the past four decades.

“Our techniques can only support natural recovery, which means that conditions have to be appropriate to allow long term survival of outplanted corals,” Petersen said.

Unfortunately, conditions in the marine tropics are becoming less and less coral-friendly with each passing year. Massive coral bleachings, brought on by too-warm ocean waters, are now a regular event. As acid builds up in the world’s oceans, it’s becoming harder for corals to secrete and maintain their calcium carbonate exoskeletons. And many corals are extremely sensitive to pollution. As we reported last year, oxybenzone, a compound found in nearly ever major brand of sunscreen, poisons corals about a dozen different ways.

Lab-grown coral is a triumph for science. But we’re going to need to do much, much more, if we want to keep the oceans liveable over the long-run.

[SECORE]

Follow the author @themadstone

Top: Reef site with intact elkhorn coral (Acropora palamata) population, via Paul Selvaggio – Pittsburgh Zoo & PPG Aquarium