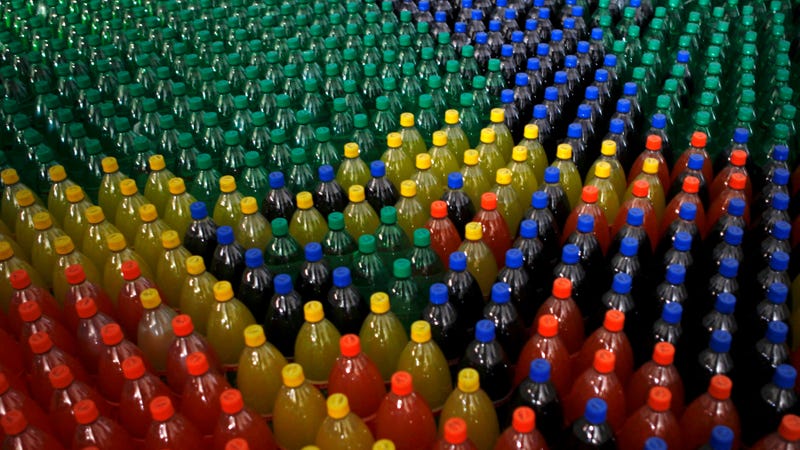

Photo: AP Images

Photo: AP Images

A real-world experiment in Berkeley, California might help settle the debate over whether taxing sugary soft drinks can make people healthier. A new study found that the drinking habits of Berkeley residents got better and stayed better over the three years after a 2014 soda tax was passed. Residents not only drank less soda, but they also started drinking more water.

Advocates of taxes on sodas and other sugar-sweetened beverages argue that higher prices will discourage people from buying the products, which are linked to obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cavities. But these so-called soda taxes have been, to put it lightly, a very controversial policy idea. Conservatives have attacked them as a nanny-state ploy to control citizens, while left-leaning critics have argued that they primarily punish poorer people. And unsurprisingly, the beverage industry has aggressively lobbied against them, too.

Politics aside, there’s not a ton of evidence as to whether soda taxes improve public health. Some researchers have argued that taxes wouldn’t actually deter people from drinking soda, or that people would compensate by eating or drinking more of other, similarly unhealthy foods.

In 2014, Berkeley became the first U.S. city to establish a soda tax, adding an extra 1 cent per ounce (the tax is technically enforced on the distributor, but they often pass on the cost to customers). Soon after, Philadelphia and Boulder, Colorado followed suit. By 2018, though, California lawmakers passed a measure that would prevent any additional local soda taxes from being passed within the state until 2031—a blackmailed bargain struck with the beverage industry after it threatened to support a ballot initiative that would make passing new taxes impossible without a two-thirds supermajority vote by local governments.

But Berkeley’s tax has remained on the books, and researchers at the University of California, Berkeley have been keeping a close eye on its effects in the neighborhood.

In 2016, members of the same team published a study looking at what happened a year after the tax was enacted. The findings were based on thousands of questionnaires filled out by residents in low-income neighborhoods of Berkeley and the two comparison cities of San Francisco and Oakland. It found that Berkeley residents drank soda and other sugary beverages 21 percent less often than they did before, while residents elsewhere actually drank 4 percent more soda.

The new findings, published in the American Journal of Public Health, show that things have gotten even better. Three years out, residents in Berkeley were drinking 52 percent less sugary drinks on average, from 1.25 servings a day down to 0.7 servings a day. Meanwhile, their water consumption also rose 29 percent. Both Oakland and San Francisco have since passed soda taxes as of mid-2017, but before then, there was no significant change in how much soda their residents drank over the same time period.

“This just drives home the message that soda taxes work,” said senior author Kristine Madsen, faculty director of the Berkeley Food Institute in UC Berkeley’s School of Public Health, in a statement.

The findings support a key counter-argument made against these taxes. While poorer people are more likely to be impacted by higher soda prices, they’re also disproportionately affected by health problems like obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cavities that are directly caused by sugary drinks. People living in low-income neighborhoods not only have fewer places available to get fresh, healthy food, but fast food and soda companies deliberately advertise more in these neighborhoods, banking on the lack of healthier food options.

Soda taxes aren’t just about making people pay more for soda, Madsen and her team argue, but signal that a change in our collective societal attitude toward these drinks is needed, much like how increasingly higher taxes on cigarettes successfully helped drive down their popularity. Adding to that, the resulting tax revenue can and has been funneled to health programs, like those for obesity prevention.

“I really want to push back against this idea that taxes are the sign of a nanny state,” Madsen said. “They are one of many ways to make really clear what we value as a country. We want to end this epidemic of diabetes and obesity, and taxes are a form of counter-messaging, to balance corporate advertising. We need consistent messaging and interventions that make healthier foods desirable, accessible, and affordable.”

[American Journal of Public Health via UC Berkeley]

Share This Story